Problem-Solution Structures Part 2

Almost all good writing begins with terrible first efforts. You need to start somewhere.

– Anne Lamott

Introducing your SOLUTION

Once you have established the need for action by writing your PROBLEM analysis, follow it up by introducing your SOLUTION.

As far as possible, limit this overview of your proposed idea to a single paragraph. Write this section primarily as a neutral/positive description focussing on the functional aspects of your solution and the benefits that will ensue. Don’t oversell! Let your solution speak for itself.

Here are some examples of SOLUTION sections. Both are written in fairly neutral terms, but the functional aspects are carefully chosen to impress the reader and to match with the key elements in the PROBLEM analyses.

Example 1: Introducing an investment proposal

Wong-Filmore Inc., one of AsiaBank’s approved financial institutions, recently proposed a yield enhancement idea of investing in a three-year Hong Kong daily accrual note. This note is principal protected. It carries a coupon for a three-month Hong Kong Interbank Offered Rate (HIBOR) plus 1.25%. Interest will be accrued daily on the condition that the daily HIBOR is set below the following barriers. If the HIBOR of a particular day is set at or above the barrier, no interest will be accrued for that day. Details of the investment are shown in Annex A.

| Year | Barrier |

| 1 | 7.50% |

| 2 | 7.75% |

| 3 | 8.25% |

Example 2: Introducing a new software package

MapInfo is a Windows software package that contains maps of various scales to which branch layouts and statistical data can be added and graphically displayed. Apart from providing management with a comprehensive database for online reference, it will also provide a visual perspective. The system can:

- aggregate information in total, by district, or by individual branch;

- link the data with maps to enable management to visually spot trends;

- analyze sales by area; and

present data on a map in tabular and chart forms.

Stating the issues

To give your reader a clear overview of your ideas, list the main issues comprising your argument in bullet form following the outline of your SOLUTION. This device will allow you to signal clearly the critical areas to be addressed by the argument for the benefit of both writer and reader.

Ordering your issues

Think carefully about how you order your issues. To create a more favorable impact in the mind of a skeptical reader you may want to balance some of these ideas:

- discuss the readers’ main concerns first;

- ‘bury’ your weakest arguments, or the most sensitive issues, in the middle of the document;

- end on a strong note.

Examples

In the Clock report (2), paragraph 5 identifies three main issues as follows.

Example 1

Tenders were invited for a mechanical, analog replacement. Granada Equipment and Supplies Ltd. (GES), agents for Templex clock movements, have been selected as the preferred supplier. The quotation has been evaluated in the following respects:

- costs

- the capability of integration with the master clock

- available designs

- quality of the product

The following examples illustrate further ways in which issues can be presented.

Example 2

The following criteria are used to assess the suitability of this note as an investment instrument:

- availability of funds

- the company’s investment guidelines

- associated risks

- estimated yield enhancement

Example 3

The project management team has taken the following issues into consideration in drawing up the list of approved tenderers:

- inclusion in the Government approved list

- the contractors’ reputation in the eyes of private developers

- opinions from the Structural Consultant

- opinions from other consultants

Example 4

Three issues need to be considered in evaluating revised membership charges:

- charges in comparable clubs;

- inflation rate; and

- past precedent.

Brief check

In effect, this list presents your analysis of the critical issues that are relevant to the case. This is the start of your EVALUATION.

Subheadings that guide the reader

Subheadings are one of your most powerful devices to signal your intentions to your reader. Most readers will glance through your subheadings before they start reading the report. This first glance must communicate both a clear structure and an informative progression of thought. Therefore, make your subheadings as precise and informative as possible.

Each of the issues identified in your list will require a sub-heading.

Generic subheadings

Imagine you have been given a policy paper to read. Possibly it has a title that attracts your attention, like:

REVISED POLICY FOR LINKING MANAGEMENT PERFORMANCE APPRAISAL TO REMUNERATION LEVELS

You look through the subheadings, and see:

- Aims

- Background

- Discussion

- Conclusion

- Recommendation

These subheadings communicate a clear structure, but you are no nearer to understanding the substance of the writer’s argument.

Specific subheadings

Now consider the following subheadings for the same paper.

Aims

Current appraisal-reward structures

Factors relating to reliable appraisal

An open-systems policy for appraisal and reward

Advantages of the open-systems approach

Recommendation

These subheadings give you both kinds of information: the structure of the writer’s argument and a general idea of its content as well. At this point, you can decide to drop the paper, or merely skim it. Or possibly, if the content is of interest, you may be drawn in to find out just what the writer means by terms like ‘open-systems’ and how this is going to affect you.

Relating issues, subheads and claims

If you carefully draft your issues list, your subheadings, and your claims (topic sentences) you can lead the reader step-by-step into your ideas. These elements in your paper help to construct a layered information structure that will allow the reader to dig as deeply into your material as is required.

Look how this example constructs five levels of information, each adding additional information.

Level 1: Issues list

- …

- …

- staff training

- …

Level 2: Informative sub-heading

A staged training program for frontline customer service staff

Level 3: Claim

A three-stage, computer-based training program will ensure that front-line staff is adequately prepared to deploy the new information system.

Level 4: Development

[Continuation from the claim into one or more paragraphs to complete this section. This may include a call-out to an Annex.]

Level 5: Annex

Annex C. Training program objectives, schedule, and costs.

[Containing detailed information about the planned training programs.]

Notice how this layered structure enables the reader to mine the paper for data, going no further into the details than required.

The Basic Information Frame used to structure sub-sections and paragraphs

You can use the Basic Information Frame to give a clear and persuasive organization to the sub-sections in your reports and proposals.

A poorly structured sub-section

Read this sub-section from a periodic report. It deals with technical development.

Example 1

Upgrade of administrative terminals

It is necessary to:

- develop additional control features on the administrative terminals in Branches, Operations Control Centre, Treasury, and Customer Services; and

- cope with the new features to be provided by the System Redevelopment Project, such as staff access control and cash control.

Management, therefore, considers that it is now essential to replace the 95 existing administrative terminals with personal computer type terminals. These will provide display/printing functions and card reader facilities that will meet the company’s current and future needs.

The organization of this section is adequate, in that it generally follows the Basic Information Frame. The passage, however, lacks persuasive power.

Use the Basic Information Frame

We can make this much more persuasive by restructuring the information to emphasize the Basic Information Frame categories. This will focus the reader’s attention more clearly on the PROBLEM-SOLUTION structure. We do this by:

- Adding a sentence at the beginning to express the MAIN MESSAGE of the section;

- Rewriting to put the PROBLEM and the SOLUTION-EVALUATION in different paragraphs; and

- Adding some positioning terms, i.e., negative words in the PROBLEM and positive words in the SOLUTION-EVALUATION. These added terms are underlined in the revision below.

An improved draft

Example 2

-

MAIN

MESSAGEWe propose replacing 95 out-dated administrative terminals in Branches, Operations Control Centre, Treasury and Customer Services with personal computers. -

PROBLEMThe current terminals lack capacity in two respects

- They cannot incorporate the necessary additional control features.

- They are incompatible with the new features to be provided by the System Redevelopment Project, such as staff access control and cash control.

- SOLUTIONIt is now essential, therefore, to replace the existing terminals with personal computers. These will provide the enhanced display/printing functions and

- EVALUATIONcard reader facilities that will meet the company’s current and future needs.

Problem-solution structures in paragraphs

Notice in the example above how the MAIN MESSAGE acts just like a topic sentence in a paragraph. In fact, we can use the same technique for writing persuasive paragraphs.

Here is a paragraph summarising the same information in a more concise form. The MAIN MESSAGE (topic sentence) is underlined.

Example 3

95 outdated terminals in Branches, Operations Control Centre, Treasury and Customer Services will be replaced with personal computers. The current terminals have insufficient control systems and are incompatible with the new features to be provided by the System Redevelopment Project. The new systems will provide enhanced display/printing functions and card reader facilities that will meet the company’s current and future needs.

Descriptive and persuasive problem-solution structures

Problem-solution structures are used in two ways: descriptively and persuasively.

A descriptive problem-solution structure explains events that have happened and solutions that have been implemented to solve problems. They are used in reporting past events and decisions. For example:

- SOLUTIONTurnover from Young Sports clothing in 199X/9X was $2.37 million, slightly lower than the previous season’s $2.45 million. To sustain customers’ interest in this range, we introduced revised designs in time for this year’s shows.

- PROBLEMThe current terminals lack capacity in two respects

- SOLUTIONThe existing branch is a leased premises from two separate landlords which has an unsatisfactory internal layout. It is prone to increase in rental values on expiration of the existing two years’ term on 8 January 199X.

- EVALUATIONManagement therefore recommends that we purchase and fit-out new premises at a cost of $45.25 million.

Brief check

Structure your argument!

Here’s a simple technique for checking whether your argument is clearly expressed and will be apparent to your reader.

Take out all the topic sentences (the claims) of each paragraph in your draft. Put them together to make a topic outline. Does the argument make sense? Revise and reorder as necessary.

Write the conclusion

Content of the conclusion

The conclusion is a short, clear statement of your judgment on the issue being discussed. It is a statement of position. At the same time, to be more persuasive, it should remind the reader of the advantages to be gained from following the action which will be recommended. These may be put together in a single paragraph, or split into two separate paragraphs.

Example

-

Statement of

positionThe planned demolition of the two offices adjacent to the main Banking Hall will cost HK$X million. It will release 750 square feet of floor space to customers, with the existing 12 service windows and six data terminals

replaced with 24 multimedia self-service terminals. The whole Hall will be renovated and its modernised layout and facilities will become more user friendly. -

Advantages to

be gainedThe net result will be an increase of 18 terminals and estimated increase in turnover from $36 million to $41.8 million (16 percent) next year. The reduction in the number of operator windows could disestablish 10 staff positions, resulting in savings of $1.8 million for the 1998/99 financial year. - SOLUTIONThe existing branch is a leased premises from two separate landlords which has an unsatisfactory internal layout. It is prone to increase in rental values on expiration of the existing two years’ term on 8 January 199X.

- EVALUATIONManagement therefore recommends that we purchase and fit-out new premises at a cost of $45.25 million.

A formal conclusion is not always necessary. By the time you reach this point in your argument, it may be that your position is clearly established already. In this case, you can move straight on from your discussion of issues to your OUTCOME.

Conclusions vs recommendations

Conclusions and recommendations are quite different in content and in function. They are related as follows:

The Conclusion section summarises the main claims of the argument. It may restate the most significant points of fact and evaluation. Generally, the conclusion will not introduce any new points which have not been previously mentioned.

In contrast, the Recommendations section deals with action. It specifies the action that should be carried out by the reader. If the reader accepts the points made in the conclusion, then the need for this action will be inescapable.

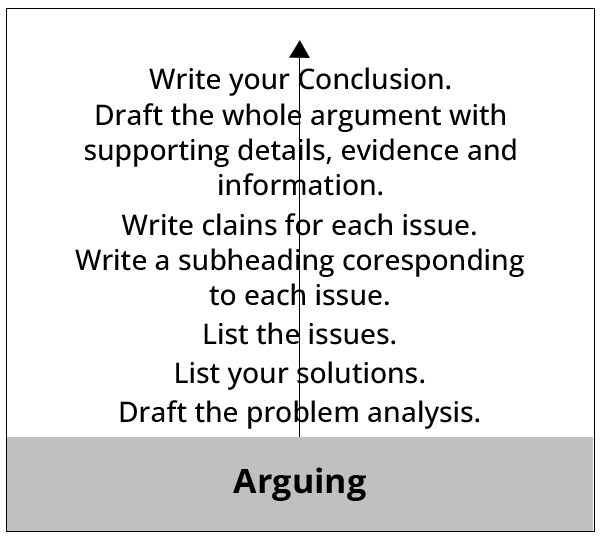

Procedures in the Arguing stage of the writing process

Think back to the diagram describing the writing process (in Foundation concepts). We can now expand this to list the steps required to put together a persuasive argument, which moves upwards from PROBLEM, through SOLUTION to EVALUATION.