Writing Single and Multiple Option Documents

The most difficult thing about writing; is writing the first line.

– Amit Kalantri

Introduction

The prime objective of persuasive reports is to help a business to take accurate and pragmatic decisions, to help reduce and resolve organizational disputes, to recommend specific action to solve a problem, etc. Depending on the reason for writing the report, single or multiple options are recommended.

This lesson presents structures for writing reports with single options put forward to address a problem. In a single option document, you will see how the EVALUATION slot can be expanded into a persuasive argument by analyzing the case into a number of critical issues.

The lesson also presents an organization for multiple option documents, i.e., reports that evaluate two or more approaches to solving a problem. The structure is based on defining clear criteria for evaluating the options. It is a further development of the Basic Information Frame and the organization of argument based on issues, claims, and evidence. We also discuss how to use matrices to approach simple and more complex decisions.

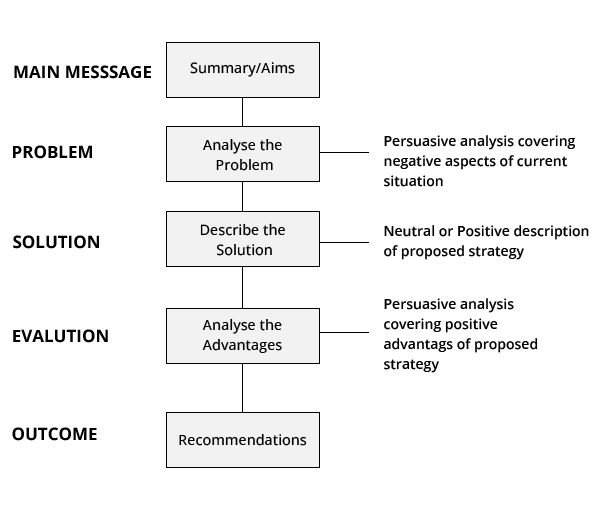

The single option structure

If you wish to discuss only a single course of action and present the advantages of this strategy, the following argument structure may be sufficient for your report. (Refer to the previous lesson The Basic Information Frame for more details). See the example below as to how the single option structure is laid out.

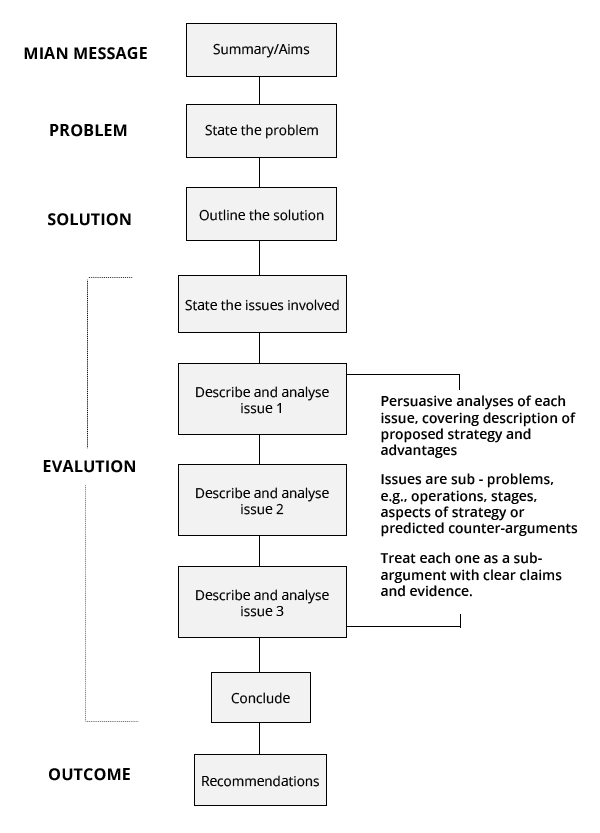

The extended single option structure

If you wish to discuss only a single course of action, but one that involves multiple issues, consider using this argument structure.

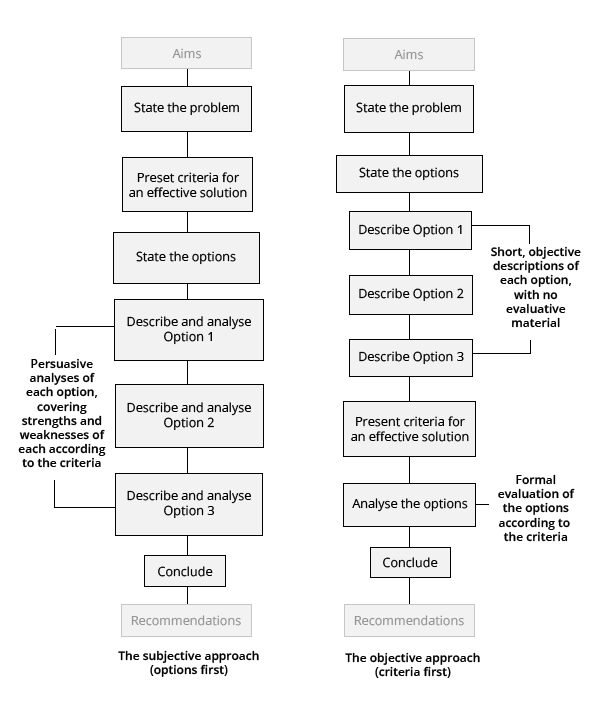

The multiple option proposal—Subjective and objective approaches

Multiple options can be presented in two ways: subjectively or objectively.

Planning a decision-making strategy

Decision-making and persuasion

One way of persuading your reader that your decision is sound is to demonstrate that the method you used to reach that decision is reliable and systematic, i.e. rigorous.

Brief check

One way in which your readers can attack your decision is to demonstrate that the method you used to reach that decision is not rigorous.

The decision-making process and the persuasion process are therefore two sides of the same coin: the technique you use for one will also serve – to some extent – for the other.

The matrix as a decision-making methodology

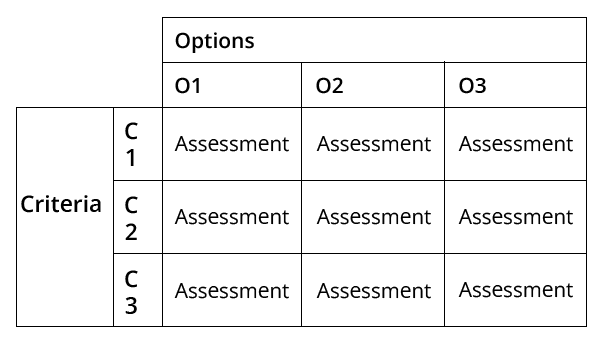

In multiple-option cases, the matrix is your main decision-making tool. Essentially this involves defining criteria and using these to explicitly evaluate each of the options.

Options

Options can be simple or complex, e.g.

- Things (e.g., purchases, three laptops)

- Strategies (e.g., three approaches to solving the problem)

- Combinations of both (e.g., strategies may imply purchases).

Brief check

A simple decision, such as assigning a contract to one of three tenders, can be approached through a simple matrix like the one above. A more complex decision may require a more complex matrix or a series of matrices.

Criteria

Criteria are derived from your problem/opportunity analysis, your objectives, your constraints, etc. Essentially they comprise the components of a cost-benefit analysis. Although we always want to maximize benefits and minimize costs, each case is likely to involve different aspects of ‘cost’ and ‘benefit’.

In any decision, try to minimize the number of criteria to 3 – 5.

When framing criteria for non-technical managers, try to avoid ‘system-focus’ (technical specifications) and focus on resource implications (costs) and productivity or service improvement (benefits). For example, the actual hard drive capacity in gigabytes is less important than the fact that the disk allows storage of complete product data for the whole company range plus twenty multimedia presentations.

Multi-level decision-making: short listing

More complex cases may require a series of decisions.

A typical example of multi-level decision-making is shortlisting. When you have a large number of options available (e.g., many applicants for a job, many models of the laptop) your first level decision is to create a shortlist. You create a shortlist by devising the first set of criteria, which enable you to eliminate as many options as possible. These criteria must result in a shortlist of 3 – 5 nearly equivalent options, all of which are feasible choices.

You then devise and apply a second set of fine criteria to identify the best from your shortlist.

Multi-level decision-making: sequential decisions

Options can also be sequential, in that one decision leads you to a second and maybe a third, all of which could be quite different kinds of decisions. For example, in purchasing new equipment to support mobile computing you may want to apply a three-level decision-making process something like this:

Decision 1: What platform (laptop, notebook, or handheld?)laptop

Decision 2: Which manufacturer? (IBM, Toshiba, Sony?) IBM

Decision 3: Which model? (Model 1, Model 2, Model 3) Model 2

Clearly, Decision 2 and Decision 3 in this sequence may also involve shortlisting.

Matrix options

You have several possibilities open as to how you construct the matrix.

- Qualitative or quantitative assessment?

- Rankings?

- Weighted or un-weighted criteria?

- Representation: numerals, ticks, symbols, colors?

Remember—the persuasive power of rigour

The most persuasive argument is the fact that you used a rigorous methodology—explicit, fair, and principled—for making the decision. A lot of your paper may be describing HOW you decided on X, rather than describing directly why X is the best.

Planning your decision-making strategy

So when you approach a multiple-option case, organize your thought following these steps:

- identify the decision-making stages that you will need to employ

- draft options and criteria for each stage

- for each criterion, define how you will assess the options